ONE OF THE GREAT ALDINE INCUNABLES

THE 1498 EDITIO PRINCEPS OF THE WORKS OF ANGELO POLIZIANO:

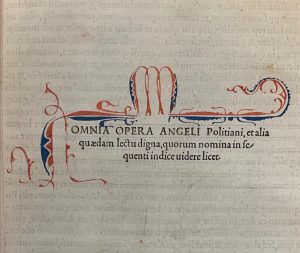

Omnia Opera Angeli Politiani, et alia quaedam lectu digna, quorum nomina in sequenti indice videre licet.

PRINTED AT VENICE IN TWO FOLIO VOLUMES IN LATIN, ITALIAN, GREEK AND HEBREW, THE FIRST COLLECTED EDITION OF ANY MODERN AUTHOR.

– from the collections of Etienne Baluze and George Abrams –

Printed in two folio volumes by Aldus Manutius at Venice in 1498, constituting not only the first collected edition of any modern author, but also the first appearance of Hebrew printing in Venice, and one of the few books printed by the Aldine Press during the Incunable Era.

Colophon reads: “Venetiis in aedibus Aldi Romani mense Iulio M. IID [1498]. / Impetravimus ab Illustrissimo Senatu Veneto in hoc libro idem quod in aliis nostris.”

Renouard calls the 1498 Aldine Poliziano ‘a rare edition, and one of the most beautiful to issue from the Aldine press’ ; the 1989 Sotheby’s catalogue of the Abrams collection of incunabula makes the following statement: “First edition and perhaps the first attempt at a collected edition of a modern author. Poliziano himself was preparing a collected edition of his letters in the last months of his life. After his death, the Bolognese humanist Alessandro Sarti took over the task; one sheet only survives of an edition begun but never completed by the Bolognese printer Plato de Benedictis. Aldus’s edition continued the enterprise, reprinting Politian’s already-published writings and translations, and adding the letters, a variety of short treatises, and Latin and Greek poems. … The square, unpointed Hebrew type that Aldus used on H8 recto was not listed by Proctor, BMC, or Haebler. It is different from the Hebrew types that Aldus used in the 1501 edition of his ‘Rudimenta grammatices,’ and so on.”

Goff P886, BMC V 559, HC 131218, Renouard 17:4, and Ahmanson-Murphy 26.

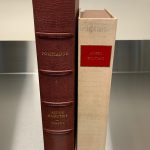

Two volume set. Both volumes are from the same edition though have travelled independently of each other for some portion of their 500+ year history. Vol. I is very tall, and in 6th century blindstamped calf, rebacked in the 20th century and with newer sympathetic, gilt-lettered spine. Text block is beautifully rubricated in red and blue with large capitals throughout and with fine scrollwork on the title page. With the bookplate of George Abrams on the endpaper, and the ownership inscription, in his own hand, of 17th century scholar Etienne Baluze, reading ‘Stephanus Baluzius Tutelensis.’ Vol. II in 16th century limp vellum with the title stenciled in manuscript upon the spine. Both volumes housed in attractive custom-made folding boxes.

Both volumes complete. 232 unnumbered leaves in the first volume, and 220 unnumbered leaves in the second volume, as called for, giving a total of 452 leaves including all blank leaves. The margins of the first volume are exceptionally wide, while those of the second volume are trimmed. Each leaf of the first volume measures about 314 mm by 211 mm.; in the second volume the leaves measure about 265 mm by 191 mm.

Very good condition both internally and externally, contents clear and bindings sound. Vol I: 20th century reback shows light edgewear, occasional spotting to contents, occasional tide marks to fore-margin. Vol. II: Minor cracking and spotting to vellum with few small chips to spine, minor foxing at the fore-edge and a spot of worming, 20th century endpapers, some marginalia.

USD $9500

PROVENANCE:

Etienne Baluze, librarian to Colbert and a great historian in own right: his signature at the foot of the title page of Vol. I.

George Abrams, 20th century typographer and collector of incunabula, whose collection was sold at Sotheby’s in 1989, and which produced one of the finest auction catalogues ever produced for a single library: his bookplate on the front endpaper of the first volume.

Unidentified (and partially scribbled-out) 17th or 18th century signature on the blank opening page of the second volume.

OF ANGELO POLIZIANO (ANGLICIZED AS ANGELUS POLITIANUS)

Angelo Ambrogini (14 July 1454 – 24 September 1494), commonly known by his nickname Poliziano (Italian: [politˈtsjaːno]; anglicized as Politian; Latin: Politianus), was an Italian classical scholar and poet of the Florentine Renaissance. His scholarship was instrumental in the divergence of Renaissance (or Humanist) Latin from medieval norms and for developments in philology. His nickname, Poliziano, by which he is chiefly identified to the present day, was derived from the Latin name of his birthplace, Montepulciano (Mons Politianus).

Poliziano’s works include translations of passages from Homer’s Iliad, an edition of the poetry of Catullus and commentaries on classical authors and literature. It was his classical scholarship that brought him the attention of the wealthy and powerful Medici family that ruled Florence. He served the Medici as a tutor to their children, and later as a close friend and political confidante. His later poetry, including La Giostra, glorified his patrons. He used his didactic poem Manto, written in the 1480s, as an introduction to his lectures on Virgil.

Politian was born as Angelo Ambrogini in Montepulciano, in central Tuscany in 1454. His father Benedetto, a jurist of good family and distinguished ability, was murdered by political antagonists for adopting the cause of Piero de’ Medici in Montepulciano; this circumstance gave his eldest son, Angelo, a claim on the House of Medici.

At the age of 10, after the premature death of his father, Politian began his studies at Florence, as the guest of a cousin. There he learned the classical languages of Latin and Greek. From Marsilio Ficino he learned the rudiments of philosophy. At 13 he began to circulate Latin letters; at 17 he wrote essays in Greek versification; and at 18 he published an edition of Catullus. In 1470 he won the title of homericus adulescens by translating books II-V of the Iliad into Latin hexameters. Lorenzo de’ Medici, the autocrat of Florence and the chief patron of learning in Italy at the time, took Politian into his household, made him the tutor of his children, and secured him a distinguished post at the University of Florence. During this time, Poliziano lectured at the Platonic Academy under the leadership of Marsilio Ficino, at the Careggi Villa.

Among Politian’s pupils could be numbered the chief students of Europe, the men who were destined to carry to their homes the spolia opima of Italian culture. He also educated students from Germany, England and Portugal.

It was the method of professors at that period to read the Greek and Latin authors with their class, dictating philological and critical notes, emending corrupt passages in the received texts, offering elucidations of the matter, and teaching laws, manners, religious and philosophical opinions of the ancients. Poliziano covered nearly the whole ground of classical literature during his tenure, and published the notes of his courses upon Ovid, Suetonius, Statius, Pliny the Younger, and Quintilian. He also undertook a recension of the text of Justinian II’s Pandects and lectured about it. This recension influenced the Roman code.

Poliziano wrote a letter to John II of Portugal paying him a profound homage:

to render you thanks on behalf of all who belong to this century, which now favours of your quasi-divine merits, now boldly competing with ancient centuries and all Antiquity.

and considering his achievements to be of merit above Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar. He offered himself to write an epic work giving an account of John II accomplishments in navigation and conquests. The king replied in a positive manner, in a letter of October 23, 1491, but delayed the commission. The epic work regarding Portuguese discoveries was only written almost one hundred years later by Luís de Camões.

It is likely that Politian was homosexual, or at least had male lovers, and he never married. Evidence includes denunciations of sodomy made to the Florentine authorities, poems and letters of contemporaries, allusions within his work (most notably the Orfeo) and the circumstances of his death. The last suggests he was killed by a fever (possibly resulting from Syphilis) which was exacerbated by standing under the windowsill of a boy he was infatuated with despite being ill. He may also have been a lover of Pico della Mirandola.

But it is just as likely that his death was precipitated by the loss of his friend and patron Lorenzo de’ Medici in April 1492, Poliziano himself dying on 24 September 1494, just before the foreign invasion gathering in France swept over Italy. In 2007, the bodies of Poliziano and Pico della Mirandola were exhumed from St. Mark’s Basilica in Florence. Scientists under the supervision of Giorgio Gruppioni, a professor of anthropology from Bologna, used current testing techniques to study the men’s lives and establish the causes of their deaths. A TV documentary is being made of this research, and it was announced that these forensic tests showed that both Poliziano and Pico della Mirandola likely died of arsenic poisoning. The chief suspect is Piero de’ Medici, the successor of Lorenzo de’ Medici and docent of Florence, but there are others.

Poliziano was well known as a scholar, a professor, a critic, and a Latin poet in an age when the classics were still studied with assimilative curiosity, and not with the scientific industry of a later period. He was the representative of that age of scholarship in which students drew their ideal of life from antiquity. He was also known as an Italian poet, a contemporary of Ariosto.

At the same time he was busy as a translator from the Greek. His versions of Epictetus, Hippocrates, Galen, Plutarch’s Eroticus and Plato’s Charmides distinguished him as a writer. Of these learned labors, the most universally acceptable to the public of that time were a series of discursive essays on philology and criticism, first published in 1489 under the title of Miscellanea. They had an immediate and lasting effect, influencing the scholars of the next century.

Anthony Grafton writes that Poliziano’s “conscious adoption of a new standard of accuracy and precision” enabled him “to prove that his scholarship was something new, something distinctly better than that of the previous generation”:

“By treating the study of antiquity as completely irrelevant to civic life and by suggesting that in any case only a tiny elite could study the ancient world with adequate rigor, Poliziano departed from the tradition of classical studies in Florence. Earlier Florentine humanists had studied the ancient world in order to become better men and citizens. Poliziano by contrast insisted above all on the need to understand the past in the light of every possibly relevant bit of evidence — and to scrap any belief about the past that did not rest on firm documentary foundations… [But] when he set ancient works back into their historical context Poliziano eliminated whatever contemporary relevance they might have had.”

OF ETIENNE BALUZE, COLBERT’S LIBRARIAN AND A GREAT FRENCH HISTORIAN IN HIS OWN RIGHT, WHOSE OWNERSHIP SIGNATURE APPEARS AT THE FOOT OF THE TITLE PAGE

Étienne Baluze (November 24, 1630 – July 28, 1718) was a French scholar, also known as Stephanus Baluzius. Born in Tulle, he was educated at his native town and took minor orders. As secretary to Pierre de Marca, archbishop of Toulouse, he won his appreciation of him, and at his death Marca left him all his papers. Baluze produced the first complete edition of Marca’streatise De libertatibus Ecclesiae Gallicanae (1663), and brought out his Marca hispanica (1688).

In about 1667, Baluze entered Colbert’s service, and until 1700 was in charge of the invaluable library belonging to that minister and to his son, Marquis de Seignelay. Colbert rewarded him for his work by obtaining various benefices for him, and the post of king’s almoner (1679). Subsequently Baluze was appointed professor of Canon law at the Collège de France on December 31, 1689, and directed it from 1707 to 1710. He was unfortunate enough to take up the history of the House of Auvergne just at the time when the cardinal de Bouillon, inheritor of the rights, was endeavouring to prove the descent of the La Tour family, in the direct line from the ancient hereditary counts of Auvergne of the 9th century.

As authentic documents in support of these pretensions could not be found, false ones were fabricated. The production of spurious genealogies had already been begun in the Histoire de la maison d’Auvergne published by Christophe Justel in 1645; and Chorier, the historian of Dauphiny, had included in the second volume of his history (1672) a forged deed which connected the La Tours of Dauphiny with the La Tours of Auvergne. Next manufacture of forged documents was organized by Jean de Bar, an intimate companion of the cardinal. These documents succeeded in duping the most illustrious scholars; Dom Jean Mabillon, the founder of diplomatics, Dom Thierry Ruinart and Baluze himself, called as experts, made a unanimously favourable report on July 23, 1695. But cardinal de Bouillon had many enemies, and a war of pamphlets began.

In March 1698 Baluze in reply wrote a letter which proved nothing. Two years later, in 1700, Jean de Bar and his accomplices were arrested, and after a long and searching inquiry were declared guilty in 1704. Baluze, nevertheless, was obstinate in his opinion. He was convinced that the incriminated documents were genuine and proposed to do Justel’s work anew. Encouraged and financially supported by the cardinal de Bouillon, he published two works with “Proofs”, among which, unfortunately, we find all the deeds which had been pronounced spurious. In the following year he was suddenly engulfed in the disgrace, and exiled from Paris to Tours, where he lived till November 1713. He continued to work, and in 1717 published a history of his native town, Historiae Tutelensis libri tres. In November 1713, he succeeded in returning to Paris, where he died on July 28, 1718.

A bust of Baluze, work of the contemporary sculptor Nacera Kainou, was installed in his native city, Tulle, in October 2006. An Etienne Baluze European Local History Prize was recently created (summer 2007) by the “Société des Amis du musée du cloître” of Tulle, on the suggestion of the French historian Jean Boutier. An international jury gave the first prize to Italian historian Beatrice Palmero. The second Baluze prize was given on May 12, 2010 to English historian Allison Carol (University of Exeter; Birbeck College).

You must be logged in to post a comment.